Earthrise—one of the best known and most widely reproduced of all science photographs—was a fluke. On Christmas Eve, 1968, after three days of space travel, America’s Apollo 8 spacecraft was on its fourth orbit around the moon when Frank Borman, the commander of the mission, began to reposition it so that the topography below could be better filmed to document potential future landing sites. During the brief time that the capsule’s windows faced away from the lunar surface, astronaut William Anders looked through them and was startled by what he saw: “Oh my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!” Anders grabbed a Hasselblad camera, loaded it with 70 mm Ektachrome film, and hastily shot off a couple of frames to capture an unanticipated and spectacular sight: Earth’s seeming ascent above the moon’s rough surface.

After splashdown on Earth and once Anders’s film was processed, one image from it, circulated worldwide by the media, left viewers awestruck. Serene, if a little disquieting, the photograph presents the marbled, blue-and-white planet’s fragile beauty that, seen from a distance, hints at Earth’s insignificance in the vastness of space. Wonder and intimations of the sublime are the frequent byproducts of science photography, and the most paradigm-changing of images can be simultaneously mind-boggling and sobering. “Wonder is tinged with awe … and it’s also tinged with fear,” science historian Lorraine Daston wrote. “It’s an uncomfortable emotion. You don’t have wonder. Wonder has you.” Once it does, and thanks to photography, we keep on looking.

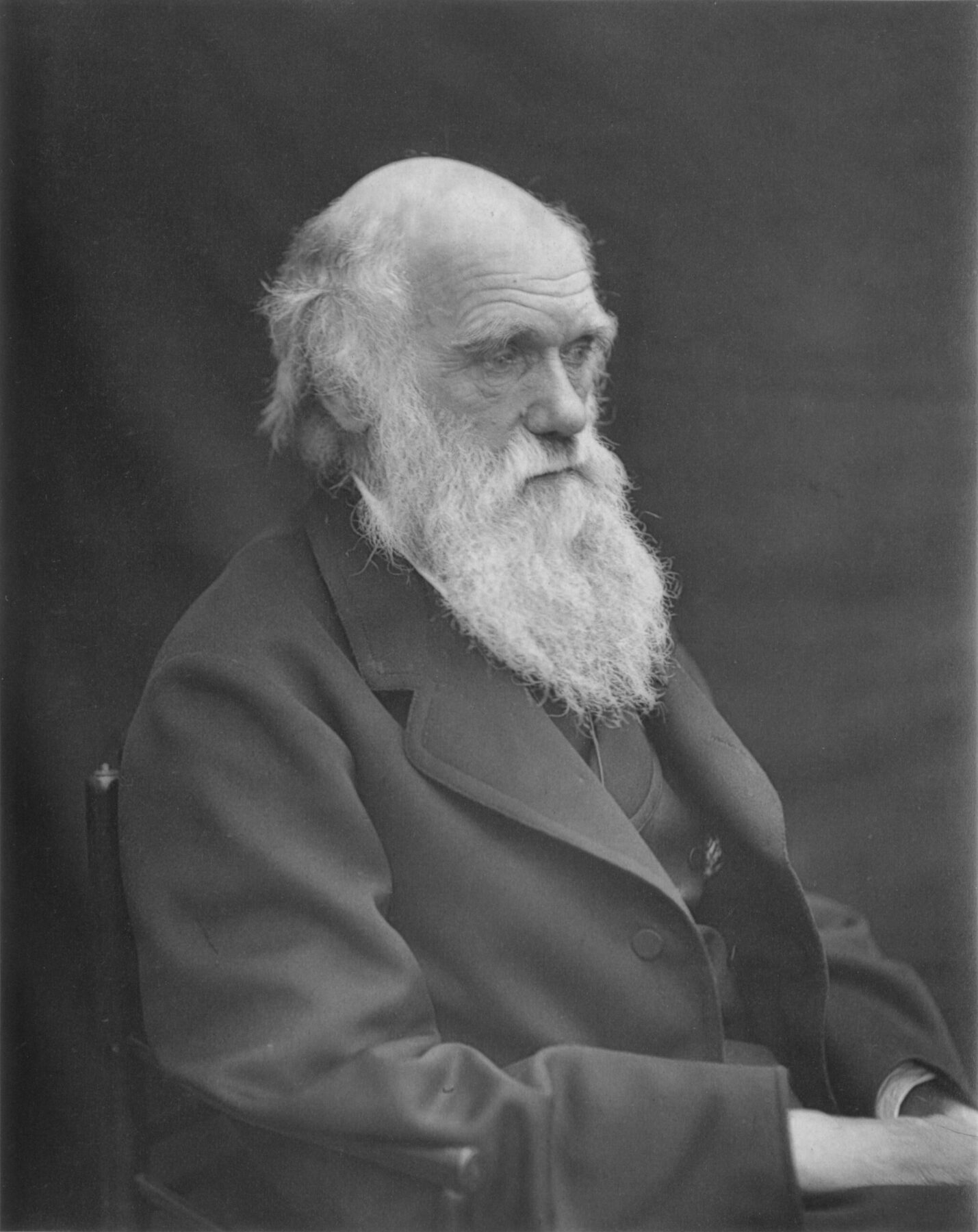

The term scientist was coined by William Whewell, a British philosopher and colleague of Charles Darwin, in 1834. Five years later, the first public use of the word photography was attributed to Sir John Herschel, the photographic pioneer who is also credited with introducing the terms “negative” and “positive” into the discourse of the new imaging medium. Ever since then, science and photography have been inextricably intertwined, two observational disciplines that reimagine and redefine each other as the need to see, and new tools for seeing, evolve. Photography, born of and shaped by science, transformed the nature of observation and stretched the parameters of knowledge and humanity’s sense of itself. Startling still images of subjects and phenomena—too small or intricate to be noticed by the human eye, too large or far away to be directly experienced, or changing too slowly or quickly for differences to be perceived— became objects of fascination and study. Photographs were immediately marshaled into service to help answer the most practical and existential of questions: What is that? Where and who are we? What happens next? Photography was deputized as one of science’s most trusted agents, essential to enhanced viewing and to making “the invisible visible, the evanescent permanent, the abstract concrete.”

Today, science imaging frames many of the challenges of our time: how to recognize and counter climate change, conquer disease and hunger, and map the brain’s neural network. Photography fuels information technologies that, soon after we create and adopt them, start restructuring our lives. In a series of controversial lectures delivered in the late 1950s, the British chemist and novelist C. P. Snow argued that the sciences and humanities represent two distinct and unbridgeable cultures. Six decades later, that gap has largely closed, as photographic images made in and of the sciences appear frequently—as news, on social media, in advertisements, in entertainment and the arts—and play significant roles in shaping public awareness, policy, and funding. Just as the sciences are altered by how images are constructed and read, so too is the public’s perception of science, its practitioners, and its impact. Science photography has moved from the background to the foreground in the twenty-first century’s field of vision, and Seeing Science presents a range of images and texts to explore how that came to pass. Traditionally, projects about the relationship of photography and science tend toward circumspection, tracking technical firsts in evidential imaging and then reflecting upon how the implications and often unintended beauty of those remarkable images intrigue and inspire artists. The goals of Seeing Science are different and twofold: to broaden the definition of science photography by expanding upon the nature of images considered, and to acknowledge some of the ways that visual culture—appreciatively, critically, and sometimes irreverently—responds.

To that end, this project surveys a spectrum of visuals that contribute to the “modern-day scientific enterprise,” underscoring the fact that science does not exist in a world of its own, but is embedded in a range of endeavors as expansive as photography itself has become. Both science and photography are observational systems with fluid borders and multiple constituencies. Images generated in fields as diverse as biomedicine, robotics, and astrophysics prove themselves to be as relevant and riveting to general audiences as to professional ones. The visionary writer Stewart Brand contends that

Science is the only news. When you scan a news portal or magazine, all the human interest stuff is the same old he-said-she-said, the politics and economics the same sorry cyclic dramas, the fashions a pathetic illusion of newness; even the technology is predictable if you know the science. Human nature doesn’t change much; science does, and the change accrues, altering the world irreversibly.

Just as what constitutes science—and science photography—changes in content and form, images essential in the day-to-day work of the sciences lead multiple lives as they reverberate throughout visual culture and influence how nonscientists come to understand themselves and others, the world they know and others that they can only imagine. Because neither science nor photography exists in isolation, Seeing Science juxtaposes images made by scientists, artists, photojournalists, commercial and stock photographers, the entertainment industry, and amateur picture takers. The range of subject matter and variety of stylistic approaches represented highlight how powerfully our engagements with the sciences are conditioned by how and where science images are encountered and represented.

Three decades ago, Carl Sagan, one of science’s proselytizers, lamented: “We live in a society exquisitely dependent on science and technology, in which hardly anyone knows anything about science and technology.” Since then, and as the sciences and our interactions with them have become increasingly frequent—and image-driven or -dependent—photographs function not only as data for, and artifacts of, the sciences, but also as the narrators and popularizers of science.

“When you’re scientifically literate, the world looks different,” astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson points out, and photography’s foundational role in teaching and promoting scientific literacy has never been clearer. And as our engagements with scientific imaging expand so have the parameters and definition of science photography. As the photographic historian Kelley Wilder observed, “There was never a photographic method, but many individual methods, each particular to a time, a scientist, or laboratory, and most importantly, to a phase in the history of photography.”

The very first photographs were labor-intensive and fragile images that rested atop chemically treated pieces of metal and paper. In recent decades, advances in digital and manipulable.” Science photography—in the shifting forms it takes, contexts it is encountered in, and ways data and meaning are extracted from it—is unique in how it impresses upon us how enmeshed in the universal scheme of things we are, and yet how limited our comprehension of and impact on that scheme of things may be.

To move science forward, more images must be made, shared, and analyzed. To maintain the momentum of, funding in, and authority of the sciences—particularly as areas of inquiry, such as environmental science, are targeted and come under political attack—images produced will need to more clearly “present science as science in action” and not as a rarified pursuit. An example of that occurred on April 22, 2017, when more than one million demonstrators gathered for Earth Day events in Washington, DC, and more than six hundred cities around the globe. The “March for Science” was organized in response to what is widely perceived to be President Donald J. Trump’s support of a “war on science,” which plays out in controversial cabinet appointments, rollbacks of protective legislation, the slashing of science advisory positions and research funding, censorship of agency reports and websites, and vociferous attempts to brand climate change as a hoax. A nonpartisan event, the march advocated for “an open and respectful dialogue about science and its impact on policy and society.” As photos of crowds and placard-bearing science workers and enthusiasts went viral, they played a strategic role in sustaining the event’s messaging and newsworthiness, illustrating yet again how photography reflects and advances the sciences’ interests and goals.

“The nature of the human mind is such,” Galileo Galilei wrote in 1610, “that unless it is stimulated by images of things acting upon it from without, all remembrance of them passes easily away.” If early in the nineteenth century, scientific observation and photography were valued as passive processes of data collection, today both are widely understood to be active and interconnected activities. As images in this project attest, science photography grounds us in the particulars of our earthly and extraterrestrial adventures, and astounds us when it reveals what lies beyond the parameters of sight, imagination, and human control. Through its stunning revelations and beauty, science photography “tells us there is nothing especially privileged about our position.” It also reminds us that, given our place in the universe, “we are eternally in ‘the middle of things.” That situation, alternately thrilling and sobering, explains why we keep on looking.